FROM THE EDITORS

It is with a little sadness but also with optimism that I give you my last issue as editor of AEMS News and Reviews. After more than three years directing the Asian Educational Media Service, I am moving on to join my husband in North Carolina and to complete my doctorate in ethnomusicology. This issue is also the last that Susan Norris, Assistant Program Director of AEMS since 2005, has contributed to. Susan left us in August to pursue a career in veterinary medicine and is already greatly missed. Although as I write this, the hiring of our successors has not yet been finalized, I am confident that AEMS will be in good hands.

When I took over from Jenny Yang as program director in 2006, she had laid the groundwork for a comprehensive renovation of our publications and programming. I am very proud of how the AEMS team has built on this to expand and diversify our programming, steadily increase our readership, and generally energize AEMS. We have piloted a new program for training scholars of Asian Studies in film-making, Digital Asia, one I hope will continue to grow. Locally in central Illinois, we have reached out to an ever wider audience of film and Asia enthusiasts with our Asian Film Festival and AsiaLENS Documentary Film Series at the Spurlock Museum, and have enormously expanded the reach of our media lending library.

All this is due to the talents and efforts of the AEMS staff I have had the honor of working with: Susan Norris, Rebecca Nickerson, Karam Hwang, David Kraus, Jason Finkelman, Rachel Lenz, and Jennifer Veile, as well as the ongoing leadership and vision of founder David Plath, former EAPS Director Nancy Abelmann, and EAPS Associate Director Anne Prescott. Our designer Evelyn Shapiro stands in a class by herself, as the only one who has worked on the newsletter since the first issue in 1998, and is the one responsible for its striking visual appeal.

But AEMS is now at another transition, overseen by the new director of EAPS Poshek Fu, and anticipating new forms and sources of funding. Digital technology and visual media and our uses of it continue to change and develop so quickly that it is already appropriate to re-evaluate again the roles that AEMS can best play in helping to bring Asia to your classrooms. I am looking forward to seeing how AEMS continues to grow into these new trends.

Our Fall 2009 issue represents perhaps a first step in the next phase of AEMS’s development as our first online-only issue. While we have, for the time being, stayed with the familiar layout and the PDF format, we have now added to the text hyperlinks to audio, video, and textual supplements. And we hope that digital distribution can increase our reach and accessibility.

This fall’s film selections center on a theme of performance. Most obviously, Vanaja and the Larry Reed DVDs deal directly with the performing arts: the former tells the fictional story of a young Indian girl’s desire to become a classical dancer, despite the limitations of caste; and the latter negotiate the tensions between tradition and change, insiders and outsiders, in the performance of Balinese shadow puppetry. A different kind of theatre is at the heart of The Great Happiness Space, the performance of love for paying customers—is it deception, or a twisted kind of art? To a lesser degree, even Up the Yangtze touches on the issue, as “China” is performed for Western cruise boat passengers, a portrayal in stark contrast to the much colder reality on the river’s shores.

I have learned so much about Asia, about film, about education and about writing in editing this publication and working with AEMS, and I hope that through our efforts you have been able to learn something new as well.

—Tanya Lee, Editor

FILM REVIEW

Daughters of Wisdom

Directed by Bari Pearlman. 2007. 68 minutes (full-length) or 56 minutes (classroom version). In Tibetan and English with English subtitles.

Daughters of of Wisdom documents the lives of a group of young Tibetan nuns living in the Kala Rongo Monastery for women in the mountainous Nangchen district of Kham, on the eastern Tibetan plateau in China’s Qinghai province. Kala Rongo Monastery was founded in the 1990s by Lama Norlha Rinpoche who grew up in Nangchen but is now abbot of Kagyu Thubten Chöling Monastery in upstate New York. Having already established schools and clinics in this area, Lama Norlha founded Kala Rongo specifically to provide Buddhist monastic education for women. Traditionally, only the sons of Tibetan families could become Buddhist monks, a decision that brought great honor to the family, while daughters were needed to work the family farm, tend livestock, and bear children. Daughters were, typically, not educated and knew little about Buddhist practice. So, when Lama Norlha presented his plans to establish the first monastic college for women in Tibet, he faced tremendous skepticism among the people of Nangchen. However, he persisted and the building of the monastic college (shedra) was completed by the nuns in 2002. Currently, nuns are attending classes at Kala Rongo in traditional Buddhist subjects, along with mathematics, science, and medicine. Daughters of Wisdom tells the stories of these committed Tibetan women. Filmmaker Bari Pearlman speaks with seven nuns ranging in age from 18 to 34 who have lived at Kala Rongo for at least six years. The women talk about their families, their decisions to join the monastery, and their daily lives at Kala Rongo, which involve such diverse activities as chanting, farming, constructing buildings, and meditating. Several discuss how their lives would be different, had they stayed with their families to herd and to raise children, and how their Buddhist practice has grown in importance during their years at the monastery.

About midway through the film, Lama Norlha is shown meeting with the senior nuns to explain that they must begin taking more responsibility for the running of the monastery complex. He instructs them in a voting process to elect eight nuns as their first Leadership Council. Though initially reluctant and shy to take on these male roles, several of the nuns acknowledge that it “might be great” to have a woman abbot. Daughters of Wisdom offers a rare window into the lives of the herding people living in a remote area of eastern Tibet and the changes introduced into their lives with the building of the monastery for women. The film allows us to hear directly from these women why they have chosen a life so different from their mothers and sisters and how Buddhist teachings have deepened their commitment to Buddhist practice.

Speaking to the camera, the nuns articulate Buddhist teachings they have learned by reading the texts and performing the monastic practices long reserved for men—truly a remarkable experience for the nuns of Kala Rongo and their community, and also for us as viewers of this remarkable transition.

In terms of classroom use, Daughters of Wisdom can be used to discuss the roles of women in Tibetan Buddhist communities both historically and in the 21st century, the impact of other cultural perspectives on Tibetan Buddhism as it moved to North America and then back to Tibet, and the importance of education within Tibetan Buddhist practice. Daughters of Wisdom can be used in a variety of classes and disciplines, including Buddhist Studies, Women’s Studies, Asian Studies, Tibetan Studies, Religion, Anthropology, and Global Studies.

Audiences from high-school age through adult will appreciate the images and voices of the Daughters of Wisdom showing their dedication to building a space for women’s religious practice in their own region and language. Filmmaker Pearlman has performed a remarkable service in documenting the transformation in attitudes and perspectives not only for the women at Kala Rongo but for all the women of Nangchen who can now choose education and a Buddhist monastic life, while still remaining on their mountain.

Catherine Benton is the Kenneth and Harle Montgomery Assistant Professor in the Humanities at Lake Forest College where she teaches classes in Asian religious traditions. She is the author of Tales of Kamadeva: Stories of Desire in Sanskrit Literature (SUNY Press) and is currently working on the religious practices of Muslim women in India.

Additional Resources

More information about the Kala Rongo Monastery, including photo essays, can be found at the NYEMA Projects website: http://nyema.org. More information about the making of Daughters of Wisdom and the filmmaker, Bari Pearlman, can be found at the film website: www.daughtersofwisdom.com.

HOW TO PURCHASE:

Daughters of Wisdom is available on DVD from Seventh Art Releasing (www.7thart.com); the DVD includes both the 68- and 56-minute versions and is priced at $59.99 for K–12 and public libraries and $349 for universities and colleges. The film is available for private use (68-minute version only) from Film Baby (www.filmbaby.com) for $25.

FILM REVIEW

Vanaja

Written and directed by Rajnesh Domalpalli. 2006. 112 minutes. In Telegu with English subtitles.

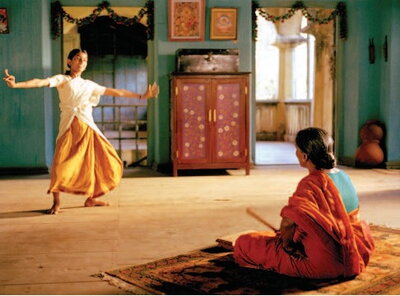

According to the first frames of this feature film, Vanaja means alternately “water lily” or “wild at heart.” It is the name of the 14-year-old girl around whom the movie unfolds and wonderfully captures her bold spirit. Like the water lily, a powerful symbol in South Asia for its ability to rise out of the muck at the bottom of a lake and emerge pure and untouched atop the water, Vanaja struggles in the film to overcome inequalities of caste, class, and gender.

There are a number of reasons to watch this film. The cinematography and scenery are exquisite. The accuracy and detail in which it portrays local Indian life is commendable. The many dance and music sequences are enjoyable and excellent for use in the classroom. These and other strengths help balance some of the plausibility issues in the plot.

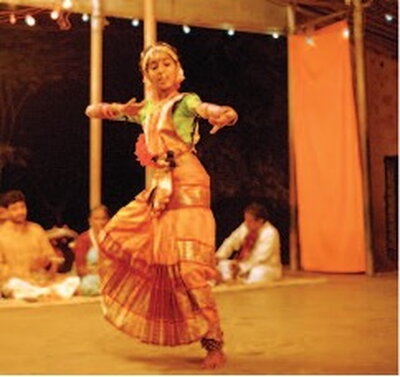

One of the most compelling elements of the film is its depiction of Vanaja’s dance training and performances. The plot centers on her deep desire to dance; in order to learn, Vanaja joins the household of her dance teacher as a servant. The style of dance she is learning is Kuchipudi, one of the eight recognized classical dances in India and the indigenous classical dance of the South Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, where the film is set. The dance is accompanied by a Carnatic (South Indian classical) ensemble consisting of musicians playing the violin, Saraswati veena (a plucked lute), mridangam (a two-headed barrel drum), and the tambura (a stringed instrument providing a drone), as well as vocalists and a nattuvanar, who conducts the ensemble through rhythmic recitation and playing of hand cymbals.

Unabridged versions of these dance scenes can be accessed independently from the DVD’s main menu. These performances would be useful additions to classroom discussion of the music and dance of India, in part because they are high-quality footage of one of India’s lesser-known classical dance styles. However, take note that the actress who plays Vanaja, Mamatha Bhukya, studied Kuchipudi for only one year in preparation for filming. These should be viewed as competent but not consummate performances.

India’s classical dances include both nritya, dance that tells a story, and nritta, non-narrative dance. A class examining the difference between these two styles might compare the first dance of the DVD, “Vasantha Tillana” with its fifth dance, “Igiri Nandini.” Characteristic of the tillana genre, the first dance performance is pure nritta, in which the singing and recitation of rhythmic, mnemonic syllables is matched by the dancer’s quick steps and angular movements. This is also Vanaja’s first public performance; students will notice her first take the blessings of the deity, Nataraja, at the front of the stage, then her dance teacher, and the earth itself.

In contrast, “Igiri Nandini” is a powerful performance focusing primarily on storytelling, or nritya. In the first section, the dancer depicts various aspects of the Goddess Durga. Short nritta sections easily identified by the nattuvanar’s recitation punctuate the portrayal of Durga slaying the demon Mahishasura, a well-known account that is celebrated in most parts of India during the festival Navaratri (see track 5 of the unabridged dances from 1 minute 25 seconds onward).

While Kuchipudi was once presented in nightlong dance-dramas where each dancer would play a separate role, today the performances have been shortened and one dancer performs the many characters involved. “Igiri Nandini” exemplifies these changes. Note that the subtitles in the third section of the performance describe the progression of the story rather than the text of the song, which consists simply of two lines sung over and over.

This film is further remarkable for its adherence to the details of local culture. In addition to highlighting the classical traditions, it opens with a performance of Burra Katha, a now endangered folk genre of storytelling. The film continues to provide rich cultural detail, such as the architecture of various homes, interior furnishings, and details right down to the kitchen utensils. There is even a scene in which the characters play ashta chamma, a board game commonly played in rural Andhra Pradesh.

Director Rajnesh Domalpalli’s close observance of rural life extended to his choice of actors; in an interview found in the DVD’s extras, the director describes the great lengths to which he went in order to cast and train working-class non-professionals for the film, which was created and submitted as his MA thesis at Columbia University.

It is advisable, however, that viewers determine how suitable elements of the plot are for younger viewers/students. Vanaja is from a poor fisherman’s caste. After one of the Burra Katha performers predicts she will be a famous dancer, Vanaja drops out of school and begins working for a wealthy retired dancer, whom she successfully convinces to teach her. Everything is going well until the teacher’s son, Shekhar, arrives home from America. After some flirtation between the two, Vanaja is raped by Shekhar. Vanaja returns home to her father, only to find him drunk and distraught at having taken on debt. She is forced to return to the mansion where the threat of Shekhar’s proximity is a heartbreaking juxtaposition with her return to the dance, illustrated in the film with stark cuts from Shekhar standing over Vanaja as she cleans the floor to her dancing the character of Radha, the quintessential female devotee pining for her beloved Krishna.

Though there are no graphic sex scenes in the film, the rest of the story deals with the aftermath of the rape. Vanaja is impregnated by Shekhar, and her father convinces her to have the child and sell it to Shekhar’s family. Not only might this story be difficult for some students to watch, but certain aspects of the remaining story strike me as somewhat implausible, particularly in the South Indian context. The film compassionately depicts many of the problems of India’s rural poor; however, subsequent interactions seem unlikely, from Shekhar’s confused attempts to court Vanaja, to Vanaja and her father’s attempts to extract more money from Shekhar’s mother, to Vanaja nevertheless being welcomed back into the house to work as her child’s nanny.

Vanaja is an important contribution to the growing list of art films coming from India and is a valuable tool for discussions among mature students about social biases and growing up in village India. There are some plot weaknesses as noted, and some concerns over the suitability for younger audiences. Its many strengths, however, make this a film well worth watching and an excellent classroom tool.

Sarah Morelli is an assistant professor of ethnomusicology at the University of Denver. She primarily performs and writes about the North Indian classical dance form known as Kathak and is currently working on her first book, an ethnographic study of the dance schools founded by Kathak master Pandit Chitresh Das.

Recommended Reading

Bhikshu, Aruna. 2006. “Tradition and Change: Transpositions in Kuchipudi” in Performers and their Arts: Folk, Popular and Classical Genres in a Changing India, ed. Simon Charsley and Laxmi Narayan Kadekar. London, New York, New Delhi: Routledge. 248–265.

Vanaja Film Website (www.vanajathefilm.com): Includes film trailer, director’s statement, information on the cast, background information on the making of the film, still photos and more.

HOW TO PURCHASE: Vanaja is available on DVD for home use from Amazon.com, priced at $21.95.

FILM REVIEW

Up the Yangtze

Directed by Yung Chang. 2008. 93 minutes. In Chinese and English with English subtitles.

The documentary film Up the Yangtze uses a short stretch of China’s 6500-kilometer-long Yangtze River to explore larger questions of economic development, human-induced environmental change, poverty and wealth, and the increasing disparities in income between China’s rural and urban areas. The movie begins with a scene of the locks at the massive Three Gorges Dam, itself a symbol of the country’s dynamism over the past two decades and of its leaders’ determination to harness the mighty river. The film’s protagonist, a teenage peasant girl named Yu Shui, is forced by the realities of peasant life to forego high school in order to make a living (and help support her parents and younger siblings) by working on a tourist cruise ship plying the swelling waters of the Yangtze.

The tension in Yu Shui’s household—between a teenage daughter who wants something other than peasant life and uneducated parents who can’t provide it—becomes clear in the early moments of the film. In one scene, Yu Shui’s mother, fighting tears, admits that it’s because she and her husband are uneducated that they have to “exploit” Yu Shui by sending her off to work on the cruise ship. As her mother talks, clearly struggling, Yu Shui silently pores over her geometry in an adjoining room, not speaking to them and seemingly already disengaged from her family. The next morning, she departs on her own, bound for the docks with a small bag of clothes and an umbrella.

Upon arriving at the dock, Yu Shui boards the cruise ship and joins a host of other young people—some from villages, others from urban areas—who will staff the vessel. Mr. Zheng, the manager, informs the recruits that it is his duty to help the “spoiled single children” by teaching them English and training them to serve the tourists—largely foreign—who come to spend their money seeing the Yangtze’s iconic Three Gorges. Yu Shui, given the English name Cindy by Mr. Zheng, is clearly out of her element, and struggles to fit in and keep up.

Juxtaposed with Yu Shui’s traumatic entry into the cruise ship tourist economy is the story of “Jerry,” a dashing young fellow from Chongqing, serving as an urbane, ultra-confident, high-school-educated foil to Yu Shui. He first appears as the bon vivant host of a drunken evening of karaoke, bragging to his city friends about his impending departure for the cruise ship the following morning and his future earnings. For him, the ship (and, by extension, the dam, the reservoir, and the well-heeled Western tourists whose generous tips he can already imagine pocketing) represents adventure and opportunity. Fortune is fickle, though, and the young man soon finds his own fortunes changed for the worse in what is perhaps the film’s only surprising turn.

For Yu Shui, the ship is uncertainty, hostility, and opportunity lost (i.e., a high school education). Periodic cuts to scenes on land remind viewers that the reality for most villagers is closer to Yu Shui’s than to that of the young man. Despite the assurances of tour guides that resettled villagers are all happy in their new villages, we meet shop owners who tell of being beaten by local resettlement officials for not having cash to pay bribes, and find Yu Shui’s farmer father, now deprived of farmland, forced to labor in a quarry. One powerful recurring image in the film is that of candles in the (presumably un-electrified) village, a poignant irony considering that the Three Gorges Dam boasts the largest hydropower generating capacity in the world.

Similarly, scenes of life and livelihoods alongside the river repeatedly contrast with the stark white markers of reservoir height set into the hillsides. Throughout Up the Yangtze, the rising waters behind the dam seem to serve as a metaphor for the growing uncertainty faced by many of China’s one billion or so rural residents. The film ends with the waters of China’s mightiest river lapping at the doorsteps of Yu Shui’s home. As her family—who end up not getting compensated—and other villagers head for higher ground, viewers are reminded that those who benefit most from major infrastructure projects such as dams, whether in China or elsewhere, are frequently people and communities far away from where the projects’ negative impacts are felt most acutely.

While at times slow, at others melodramatic, Up the Yangtze offers a great starting point for more focused and nuanced discussions of the environment-economy-culture nexus in China. I have used the film in my sophomore-level college course “Environment and Development in East Asia,” and it would likely work equally well in a high school course.

Darrin Magee is assistant professor of Environmental Studies at Hobart & William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York. A geographer by training, his particular area of expertise is water and energy in China, including hydropower and the South-North Water Transfer. At HWS he teaches courses on environment and development in East Asia, water resources, garbage, human geography, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS).

Recommended Resources

Background facts, including the history of the Yangtze River and the Three Gorges Dam, maps, and a series of interviews with the director are available at www.uptheyangtze.com.

HOW TO PURCHASE:

Up the Yangtze is available for purchase on DVD from www.zeitgeistfilms.com. Price for institutions is $195 and for home use is $29.99.

FILM REVIEW

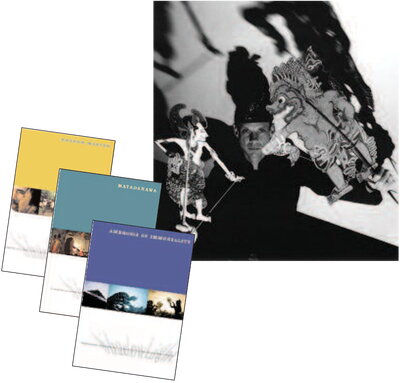

Larry Reed’s Balinese Shadow Puppetry Films

- Shadow Master Directed by Larry Reed. 2006, 1979. 54 minutes.

- Mayadanawa Directed by Larry Reed with I Nyoman Catra. 2007. 27 minutes.

- Ambrosia of Immortality Directed by Larry Reed and I Wayan Wija. 2006. 36 minutes.

All three films produced by ShadowLight Productions. In English and Balinese with English subtitles.

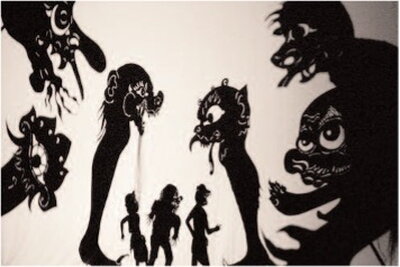

Shadow master Larry Reed (above) "integrates the power and mystery of shadows, the scale of film, and the immediacy of live performance."

The Indonesian island of Bali has a long and rich tradition of shadow puppetry, a dramatic art form found across Southeast Asia. Many Balinese understand shadows to be links between seen and unseen realms. Shadow plays are often performed for religious purposes, to aid in the balancing of conflicting forces. Conflicts between tradition and modernity and between Bali and the West play out in each of these three DVDs created by ShadowLight Productions.

Filmed in Bali in 1979, Shadow Master portrays a “dramatization of events” over two years when American Larry Reed was there studying wayang, or shadow puppetry. The film follows two brothers, Kadek and Ketut, and is narrated in English by Sylvia Tiwon playing the voice of the puppetmaster’s daughter, Made. Kadek is dedicated to learning to be a puppeteer with the master I Nyoman Radjeg, while Ketut is interested only in girls and motorbikes. The contrast between the brothers’ priorities embodies a tension between Balinese traditional culture and modern influences. In following the brothers through their days, many aspects of Balinese life are represented. Scenes include performances of dance and drama, a cockfight, classroom teaching, and parts of a ngaben, or cremation ceremony. Students should be forewarned that a corpse is shown as it is being prepared for the cremation, as these scenes may be disturbing to some viewers. This historically vibrant film captures Balinese domestic and artistic life of 30 years ago and shows current masters of the performing arts, such as puppeteer (and field producer) I Nyoman Sumandhi, as young adults. In one striking scene, we see the puppeteer and musicians walking on foot to a performance carrying their instruments, puppet box, and oil lamps hanging from poles resting on their shoulders; these days, most performers travel by car, truck, or motorbike. Some elements of the film, however, are still profoundly relevant today, including its emphasis on learning and the wise advice given to students by their elders regarding the intricacies of improvising drama and comedy.

One scene in particular serves as a microcosm of the changes in Balinese culture, then and now: as Kadek finishes his first public wayang, everyone sitting behind the screen turns 180 degrees to face a television at the opposite end of the space.

Shadow Master leaves some questions unanswered. Does Kadek become the next great puppeteer? Does Ketut ever settle down? Does Balinese wayang survive the competing influences of television and other media, and if so how? This last question is at least partially answered by Reed’s later collaborative development of shadow theater. Reed has expanded the use of wayang to contexts far beyond Indonesia, including portrayals of California history, and Native American and Chinese myths and legends. The next two DVDs discussed, however, showcase his collaborations with Balinese artists.

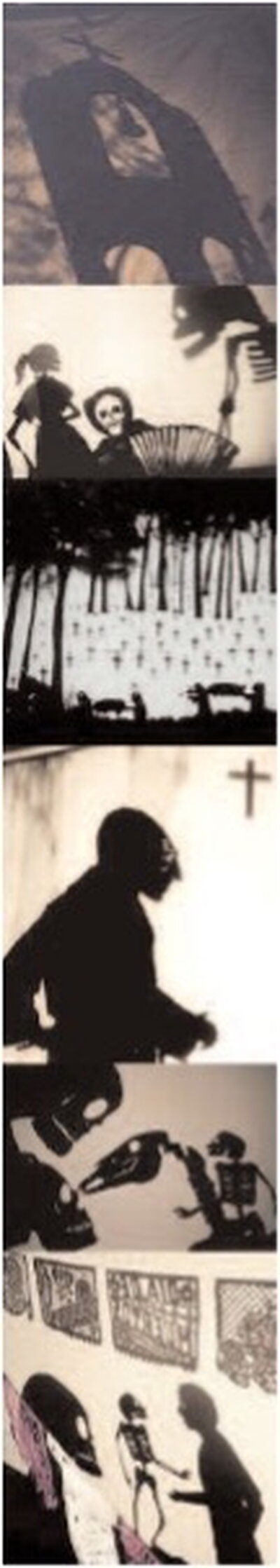

Mayadanawa and Ambrosia of Immortality also address tradition and change, but rather than mutually exclusive opposites, they are portrayed as potentially compatible. These DVDs feature some of the important figures who have been at the forefront of pushing the boundaries of Balinese performing arts but who have also been some of its strongest guardians and advocates. Each DVD includes edited performances of wayang listrik, or electric shadow play, and a brief documentary about the making of each production. Ambrosia of Immortality also includes a slideshow with still photos from the performance.

The latest ShadowLight production is “Ghosts of the River” which opened at Teatro Vision in San Jose, California, October 2009. Here is aclose-up showing a set of masks created by art director Favianna Rodriquez.

Historically significant as the first wayang listrik to be produced in Bali, Mayadanawa and the interviews with Reed in the 10-minute accompanying documentary elucidate the early development of wayang listrik. The Balinese legend of Mayadanawa, a demon who demands people to forsake their gods and worship only him, was performed and filmed in Bali in 1996. The project involved several renowned Balinese artists, including puppeteer I Made Sija; I Dewa Putu Berata, currently the director of Gamelan Çudamani; and musicians from the village gamelan of Pengosekan. The edited performance of Mayadanawa includes perspectives from behind the screen, as well as footage from preparations and rehearsals. The performance is in Balinese, though subtitles in the video are clear and well paced.

Ambrosia of Immortality was performed and filmed in the US in 1998. Intended for an American audience, the performance is mainly in English. Involved in the production are musicians from the American-based Gamelan Sekar Jaya and several Balinese performers. The 14-minute “making of” documentary includes interviews with Reed, Berata, and performer Emiko Susilo.

Innovations in both productions include the ability to create whole landscapes, a vast range in the scale of characters, projections of humans alongside puppets, and the use of mirrors to create light images on the screen. For example, overlapping silhouettes of dancing girls and a priest’s bell symbolize the aesthetic of a festive and bustling atmosphere, crucial to Balinese religion and art.

Behind-the-curtain view at a “Ghosts of the River” rehearsal.

Both of Reed’s productions bring the unseen realm to life, making visual what previously was only referred to, implied, and imagined. These DVDs are appropriate for use in high school and college and should spark discussions of Balinese Hindu mythology, theater production, concepts of tradition, and social/artistic change. They would benefit those interested in shadow puppetry, Indonesian performing arts, and contemporary theatrical design. They could be shown separately, or Shadow Master could be shown with one or both of the wayang listrik DVDs. Showing the documentary portion of Mayadanawa and/or Ambrosia before the respective edited performance would be the most useful for students. The videos do not include much direct critical discussion of Reed’s role as a foreign influence, though his collaboration with Balinese and other artists is clearly emphasized. Battles between tradition and modernity depicted in Shadow Master are somewhat resolved as the two come together in innovative, cross-cultural productions on the other DVDs.

The harpees attack in a scene from “A (Balinese) Tempset,” an adaptation of Shakespeare’s magical play, produced by ShadowLight.

Wayang listrik has become influential in Bali, as puppeteers and performing artists have incorporated and further expanded these concepts and techniques, developing their own creations.

Sonja Lynn Downing has spent over a year and a half in Bali, Indonesia, studying Balinese gamelan and conducting research on gender issues in children’s gamelan ensembles. She received her Ph.D. from the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 2008 and is currently a postdoctoral fellow of ethnomusicology at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin.

In performing “Ambrosia of Immortality,” shadow masters I Wayan Wija and Larry Reed lead a cast of nine masked actor/shadowcasters. Fivemusicians create the sound of a full gamelan orchestra by combin- ing live instruments and digital sampling.

Recommended Resources

Short videos and introductions on these films are available at http://www.youtube.com/user/shadowlightproductns and are also found on the ShadowLight website.

HOW TO PURCHASE:

Shadow Master, Mayadanawa, and Ambrosia of Immortality are all available for purchase at the ShadowLight Productions DVD Store (http://shadowlight-store.semkhor.com). Institutional price for each is $150 and home viewing price for each is $30. The DVDs are also available as part of an 8-disc boxed set, Explorations of the Shadow World, priced at $800 for institutions and $200 for home viewers.

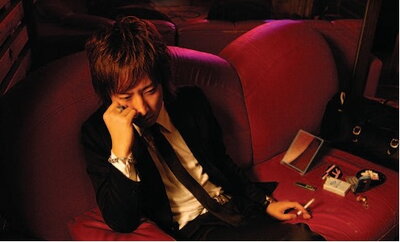

The Great Happiness Space: Tale of an Osaka Love Thief

Directed by Jake Clennell. 2006. 75 minutes. In Japanese with English subtitles.

Outside Japan, few people know about the world of host clubs, where women buy the attentions and sexual services of handsome young men. The Great Happiness Space, a documentary directed by British filmmaker Jake Clennell, takes the viewer into this little-known and often misunderstood underworld. The film follows a day in the life of Issei, owner and top host at Club Rakkyo in Osaka. Beautifully shot and edited, and eschewing sensationalism or prurient voyeurism, Clennell captures the humanity and complexity of both the hosts and their customers.

The film’s greatest strength is that Clennell himself does not intrude in any way—there is no voice-over narration. The entire film is a series of intermingled interviews with Issei, several of his hosts, and many of the female customers. There are a few shots of customers at the club, and a few brief scenes of a prospective host interviewing for a job, but for the most part, the hosts tell their own story. At first this gives the film a loose, rambling feel, but as the interviews continue, and we discover more about who the customers are and how the hosts feel about their work, a heartbreaking human drama gradually emerges.

Because the film unfolds without much introduction, viewers unfamiliar with the topic are likely to begin with some misconceptions about host clubs—in particular, about who the clientele is. In the US we tend to think of male prostitution as a bizarre, almost mythical aberration, the customers being wealthy older women who for some reason could not attract men by “normal” means. However, this is not the case in host clubs; the women are for the most part young and attractive. The film does not reveal who these girls are until about halfway through, but in fact nearly all the clientele of host clubs are women involved in the sex trade themselves, as prostitutes, hostesses, strippers, call girls, and the like.

For this reason, the host clubs are less an equalizing mirror image of hostess clubs than a parasitic offshoot. A mainstay of the Japanese nightlife and socializing for salarymen, hostess clubs are bars where men pay to have hostesses serve them drinks and flirt with them. Although it’s not outright prostitution, men are expected to form relationships with particular hostesses and to meet them outside the bar, trading expensive gifts for sexual favors. Because the exchange of sex for money happens at a different location, when the women are off the clock, hostess clubs manage to avoid anti-prostitution laws. The host clubs function in a similar way: the women pay enormously inflated fees for drinks in order to spend time with hosts who flirt with them and flatter them. The women in the sex trades find it easier to relate to men who are doing the same thing and who don’t judge them for it.

The women seem less interested in sex than in an emotional relationship with the host. Although a woman might flirt aggressively and ask the host to take her to a hotel, Issei claims that once he has sex with a client, she won’t return. And because the women are having sex with men they don’t like for money, what they really want in their off-hours is a man who will pay attention to their emotional needs, and say he loves them, even if they know it’s not real. Hence the subtitle, Tale of an Osaka Love Thief. What the hosts are really selling is not sex but love, or the illusion of love.

All this fakery and buying and selling of sex and intimacy seems to take a toll on both the men and the women. At one point, Issei comments that he would like to have a real girlfriend but that he’s spent so much time pretending to be in love, he’s not sure if he could have a genuine relationship anymore. He’s not even sure where the host ends and his real self begins.

When the film begins, Issei and the other hosts seem full of macho bluster about their sex appeal and the money they earn, but by the end, when we see them stagger home in the morning, exhausted and sick from a night of binge drinking, it’s hard not to feel sorry for them.

Because of the subject matter, The Great Happiness Space is only recommended for college-age audiences. Most of the interview subjects slip in and out of Osaka dialect, and use a lot of slang, which may be hard for language students to follow. However, the film lends itself well to discussion not only of sex work but larger issues of gender relations, both in Japan and in comparison to other countries. Although there are no academic studies of host clubs yet, anthropologist Anne Allison’s study of hostess clubs can place the film in context. The film raises some provocative questions: Who is profiting from Japan’s massive sex trade? Are the women empowered by visiting host clubs, or do those clubs simply reinforce gender inequality? By letting the subjects speak for themselves and not inserting his own answers, director Clennell leaves viewers to draw their own conclusions.

Deborah Shamoon is assistant professor of Japanese literature and film at the University of Notre Dame. Her research focuses on girls’ culture and shojo manga (girls’ comics) in Japan.

Recommended Reading

Allison, Anne. 1994. Nightwork: Sexuality, Pleasure and Corporate Masculinity in a Tokyo Hostess Club. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

HOW TO PURCHASE:

The Great Happiness Space is available from Amazon sellers at amazon.com and amazon.ca, generally priced at $20 to $30.